What is a company’s largest source of greenhouse emissions? For most businesses, the answer lies in their value chains. Or rather, the tangled net that is their value mesh.

Scoping the Problem

When you think about sources of a company’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, the first thing that might come to mind is emissions associated with its facilities: its factories, warehouses, and offices. If the company is in the transport sector (e.g. a courier company or an airline), you might think about the emissions from its vehicles. If so, you’re thinking about the company’s scope 1 and 2 emissions.

Country level GHG measurement standards were defined by the UN’s Framework Convention on Climate Change, which stipulates which types of gases need to be measured and the Global Warming Potential (GWP) of each. The GWP assesses how powerful the warming impact of a unit of a given gas is over a specified period of time. For example, a kilogram of methane released into the atmosphere has over 80 times the warming impact of a kilogram of carbon dioxide over a 20-year period. Some refrigerant gases have GWPs in the tens of thousands.

As an aside, most GHGs persist in the atmosphere for many centuries or millennia, so cumulative emissions count: if we achieved zero emissions globally tomorrow, the climate would just stop getting hotter. It wouldn’t revert to where it was, say, 100 years ago, unless we achieved negative emissions and actually reduced the concentration of GHGs in the atmosphere.

In turn, corporate GHG measurement standards are defined by the GHG Protocol Initiative, which was established by the World Resources Institute and World Business Council for Sustainable Development. The Protocol established three “scopes” of emissions:

1. Direct emissions associated with facilities and vehicles directly controlled by the company. Typically associated with the combustion of fossil fuels (such as natural gas, oil and its derivatives petrol and diesel) or releases of GHGs related to various chemical or biological processes, such as cement production or fertiliser use. Leaks of GHGs such as methane (natural gas) and refrigerant gases from equipment or pipelines owned by the company are also counted – these are known as “fugitive” emissions.

2. Purchased energy in the form of electricity, steam, heating or cooling that is used by the company. A company measuring its emissions needs to understand the “emissions intensity” of the energy sources it purchases. This is assessed in terms of how many kilograms of GHGs (typically normalised as “kg CO2-equivalent”, where the warming impact of the various GHGs is baselined to the equivalent impact of a kg of carbon dioxide) are used to produce a particular unit of energy. For example, in a power grid dominated by bituminous coal electricity generation, a MWh of electricity might produce around 800kg of emissions.

3. All other emissions associated with what the company does.Scope 3 is where it gets complicated. Because you’re needing to measure the full upstream and downstream value chain of the company. Effectively, its sphere of influence: what emissions would not be produced if that company did not exist (regardless of whether competitor firms simply sold more in that case). And when you set out to do that, you quickly realise that the term “value chain” is altogether too linear. It’s really a “value mesh”.

The Value Mesh Challenge

A manufacturing client I work with purchases over 1,000 items that go into its products, from hundreds of suppliers located around the globe. In all cases, those suppliers themselves source inputs from other companies, who in turn source inputs from other companies, and so on back to the raw materials providers. In addition to emissions directly associated with producing the input, each of those suppliers has emissions associated with their facilities, electricity, employee commuting, business travel, waste, transportation of products, and many more. It’s easy to see how the upstream value chain is more of a tangled net.

And it’s by far my client’s largest source of emissions. These upstream sources are known as “embodied emissions”. Though it’s very difficult to measure the entirety with any accuracy, given a lack of well-regulated emissions data for many companies; and a purchaser typically having limited influence over their suppliers (unless they happen to be a giant in their sector, like Coles or Woolworths are in Australian FMCG).

Indeed, contractually it may be almost impossible to get information about a supplier’s ownsuppliers, let alone untangling any further up the mesh. As such, measurement of upstream value chain emissions typically relies on proxy metrics, using datasets that associate an emissions factor to dollars spent on different types of supplies.

This simplification may mask wide variation between the relative emissions intensity of different companies producing the same supplies. For example, if one aluminium smelter uses renewable electricity while another uses coal, their emissions intensity for a kg of aluminium would be chalk and cheese.

When Downstream Counts More

On the other hand, for some industries, including fossil fuel energy supply and automotive manufacturing, the largest source of their scope 3 emissions is the downstream value chain, particularly customers’ use of their products. In this case, it is relatively easy to see that a company that exclusively produces electric vehicles rather than petrol/diesel should have lower scope 3 emissions (knowing that charging the vehicles’ battery from grid power largely sourced from coal generation is typically less emissions intensive per kilometre travelled than even an efficient internal combustion engine).

In terms of an electric vehicle manufacturers’ overall emissions, the embodied emissions of the materials used to make the battery and electric motors need to be compared with the equivalent emissions for a petrol/diesel vehicle’s engine, starter motor, radiator, gearbox, fuel tank, battery, etc. Typically, an EV is somewhat heavier than an otherwise equivalent internal combustion model, but only by about 10%. Nevertheless, all of these factors, along with the end-of-life arrangements – such as the recyclability of the vehicle’s parts – need to be taken into account in assessing the manufacturers’ total emissions.

A franchise business model might also have large downstream scope 3 emissions, since franchisees’ operations and supplies count as part of its sphere of influence, even if the master franchisor has a relatively small direct footprint.

Investment Emissions

Another potentially large source of a company’s scope three emissions, and one that is seldom considered, is its investments. Where are its free cashflow and reserves invested? If they’re in deposit accounts of banks that lend to emissions intensive industries (such as fossil fuel firms), or in equities or bonds issued by emissions intensive firms, then that could be material (in which case it should require disclosure). Financial services firms have come under intense scrutiny over the last decade given their facilitation of high emitting activities, and companies with large cast reserves are starting to be examined by various think tanks and activist groups.

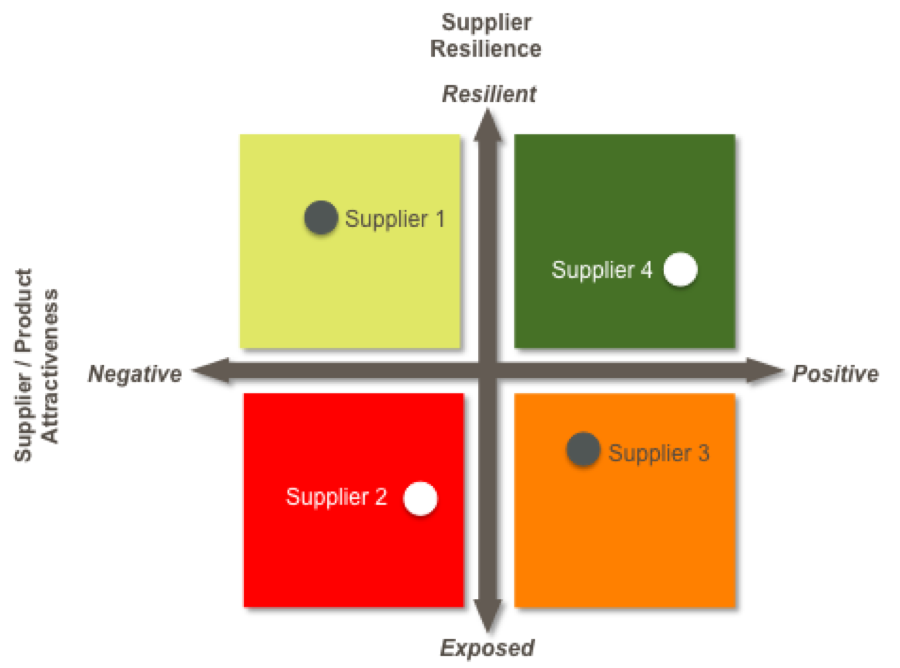

If You Have Value Chain Influence, Use It Wisely

Purchasing power is a function of how much a company buys as a proportion of the total market for the particular good or service. As mentioned earlier, the supermarket giants in Australia control a significant proportion of the total spend on entire product lines and industries. Companies with high purchasing power are in the position to transform industries towards low emissions intensity. Or to force a switch to low emissions substitutes.

But your company needn’t be a behemoth to have positive influence. Simply modifying your standard RFP (request for proposal) procurement clauses to make a supplier’s commitment to sourcing its electricity from renewable sources a desirable (or even mandatory) requirement can make a difference. If nothing else, it will make that supplier think about it.

In addition to renewable electricity, some key questions to ask major suppliers could include:

- Outline [supplier’s] plan to achieve net zero GHG emissions including the target date and emissions reduction achievements to date.

- Has the net zero plan been endorsed by the board and publicised? Is it aligned with other strategic plans? Is executive remuneration tied to the achievement of the plan? To what extent has funding been committed to implement the plan?

- Is the plan endorsed by the Science Based Targets Initiative?

- What proportion of the planned move to net zero is accomplished by genuine emissions reduction vs use of purchased carbon offset credits?

- Explain the extent to which scope 3 value chain emissions are included in the net zero target. How they have been measured or estimated? What upstream/downstream emissions sources are excluded?

- Have your major suppliers made net zero commitments at least equivalent to yours?

These types of queries will provide a useful reference to baseline and track upstream value chain progress over time. Including contractual clauses requiring updates and evidence of key suppliers’ emissions reduction achievements is also useful.

Measuring and driving down value chain emissions is a critical step towards delivering net zero emissions. But it requires effort and tenacity.

David McEwen is a Director at Adaptive Capability, providing TCFD-aligned climate risk, and net-zero emissions (NZE) strategy, program and project management. He works with businesspeople, designers and engineers to deliver impactful change, and has delivered dozens of property-related projects. His book, Navigating the Adaptive Economy, was released in 2016.