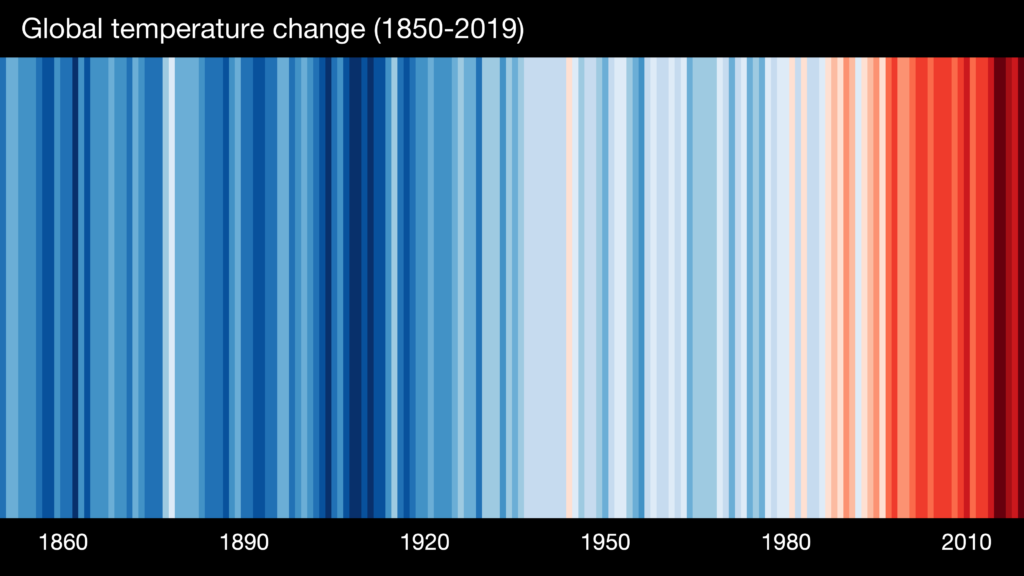

From 1 July 2024, the Australian Government intends to require mandatory disclosures of climate related financial and non-financial data in company annual reports, in what is one of the most significant corporate reporting shake ups in decades. It is designed to clearly quantify all emissions including end-use of a company’s products, a first for Australia. One company’s end product is another’s input, so there is likely to be some virtuous contagion that will occur as emission intensity becomes another factor like price in product selection.

The changes will affect both listed and private entities, starting with larger firms in 2024 (and those that are already required to report their emissions), but with the net tightening over the following four years to include (by the 2027/28 reporting year) mid-sized companies that meet at least two of the following thresholds: over 100 employees; $25m+ in gross assets; and/or $50m+ in consolidated annual revenue.

Companies will be required to consider material emissions along their full value chain, from raw materials extraction and intermediate processing, to emissions arising from the downstream use and disposal of their products or services. These so-called Scope 3 emissions typically account for most an organisation’s total climate impacts. Various databases and proxy measurement methodologies are available for estimating Scope 3 emissions, but increasingly, companies will be expected to be able to provide their customers with externally assured data breaking down emissions sources and providing estimated emissions per unit or dollar spend.

Based on the International Sustainability Standards Board’s (ISSB) climate standard, IFRS S2, the new requirements will be formalised over the next few months, following consultation earlier in the year. Building on the disclosure framework originally proposed by the Taskforce for Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) in 2017, IFRS S2 adds more specific and onerous qualitative and quantitative disclosures around governance, strategy risk management, metrics & targets, and the location and timing of reports.

The exact details of the Australian implementation will be contained in new Australian Accounting Standards Board (AASB) standards, expected to be finalised early next year. Quantitative analysis and levels of external assurance will be phased in, to give companies and their boards a bit of breathing space as they develop competency with the complex requirements.

The new disclosure standards are expected, in conjunction with other initiatives being undertaken by the ACCC and the Department of Climate Change, Energy, Environment and Water (such as the recently announced reform of its Climate Active certification scheme), to provide investors, customers, competitors and other stakeholders with much more comprehensive data and information about firms’ emissions intensity and climate risks, and the credibility of their plans for reduction and risk management. Greenwash will become much easier for regulators and others to identify and call out.

As ISSB Vice-Chair Sue Lloyd has said, “Companies should do this not because they’re forced to – but choose to – because it’s a great way to communicate to the market and attract capital.”

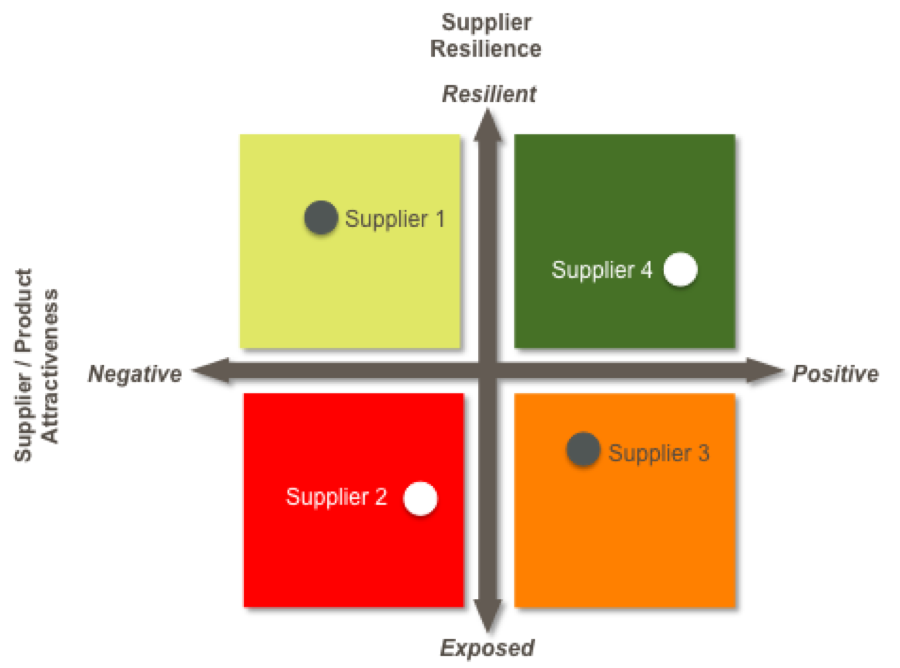

Even if your business is not caught in the disclosure net, expect those B2B clients who are to demand disclosure of the emissions intensity of the products and services you supply, along with your trajectory towards net zero greenhouse emissions. Companies with lower emissions intensity and a clear and compelling pathway to net zero will be at an advantage. If your business represents a material component of their value chains, expect them to request a breakdown of your climate risks and associated controls to feed into their own reporting. And if you’re seeking capital, bankers and other potential investors are likely to begin to require such disclosures.

Not sure where to start? Contact us for a complimentary confidential briefing session to help you ascertain where you are in your climate reporting journey and recommended next steps to prepare.

With major regulators making increasingly direct and clear statements about directors’ liability relating to the management of climate change risks, the “unforeseen” excuse is no longer going to cut it. In recent months major Australian regulators the RBA, APRA and ASIC have made it clear that the implications of climate change must be effectively considered in corporate decision-making.

With major regulators making increasingly direct and clear statements about directors’ liability relating to the management of climate change risks, the “unforeseen” excuse is no longer going to cut it. In recent months major Australian regulators the RBA, APRA and ASIC have made it clear that the implications of climate change must be effectively considered in corporate decision-making.