Despite multiplying public pressure, global action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions is currently falling substantially short of the levels necessary to avoid dangerous climate change. How will we adapt?

Most people broadly understand climate scientists’ predictions that, as global average temperatures continue to warm, the consequences will include extreme weather of increasing frequency and/or intensity; rising sea levels due to ice melt; consequential loss of biodiversity; and a range of other implications. But relatively few have thought about what that means to the way we live, and what we might need to do to adapt.

Anathema to Imperative

I started researching my book, Navigating the Adaptive Economy, in 2013. In those days, even after the failure of COP15 in Copenhagen to reach agreement on emissions reduction in 2009, it was still almost anathema to talk about adaptation: we were going to beat climate change and therefore adaptation wouldn’t be required. Mentioning it felt like a sign of defeat.

Only six years later and despite the landmark Paris Agreement of 2015, global emissions are still rising[1]. According to the IPCC[2] we stand at a cross roads. Without an emphatic change of political direction in the next 12 months, there is very little chance of maintaining a safe climate during the remainder of this century. As such, talk on adaptation now takes centre stage.

An example: the recently released report from the Global Commission on Adaptation[3], which tries to talk up public and private sector investment in adaptive measures by painting a picture of positive returns on investment in early warning systems, resilient infrastructure and water supplies, agricultural productivity, and natural coastal defences. Most of the benefits involve future cost avoidance – adaptation as a form of insurance, though in this case for an outcome that will almost certainly happen, rather than one with a relatively low likelihood of occurrence.

The next few decades will be marked by cycles of “fight” adaptation to sea level rise, followed by an eventual, belated realisation that abandonment and retreat is the only sensible long term course of action.

However, there’s a big challenge with adaptation: matching planning time scales with expectations of climatic change.

Rising Seas: Rising Challenges

Take sea level rise (SLR). Five years ago Miami Beach, Florida spent US$500 million raising roads and seawalls at Sunset Harbour about 75cm and installing 80 pumps to avoid so-called “sunny day flooding”, when king tides back flow through storm water drains and flood the streets[4]. That’s a temporary, localised solution at best, for a coastline exposed to some of the highest rates of SLR in the world (currently just under 1cm per year; due to currents and local coast and seabed conditions rates of SLR vary considerably). The city has recently committed a further half billion dollars to raise additional vulnerable streets and is considering a plan to convert a golf course to wetlands to assist with storm-water drainage[5]. As a wealthy municipality it can currently afford this sort of expenditure, but for how long?

Locally, 55 coastal communities in West Australia alone are at risk of property and infrastructure damage from coastal erosion[6], with storm surges being amplified by Australia’s more modest sea level rise of just over 2mm per year over the past half century (but accelerating)[7]. What to do?

A difficult task for local and state government planners is deciding what level of SLR to assume over an infrastructure planning horizon of 50-100 years. Future climate projections are tricky for two main reasons: one is, we don’t know what humanity is going to do about emissions reductions; the second is that it’s difficult to predict at what point we might trigger natural positive feedbacks that amplify warming and/or the rate of SLR. Based on various assumptions about emissions and the response of the climate system, average SLR by 2100 could be anywhere from less than 50cm to potentially over 2 metres – a massive variation[8].

And it’s more complex, because a lot of potential coastal property damage is in conjunction with storm surges. The intensity and direction of the storms is affected by other climate change assumptions about ocean warming and atmospheric moisture retention; SLR then becomes a multiplier in terms of how much damage and how often.

Fight or Flight Cycles

At the current stage in our evolution, humanity’s fight vs flight response seems to tend towards the former. So for a number of decades to come it feels likely that in many locations we will choose to attempt to defend coastal cities and homes from encroaching seas, through a combination of “planning denial” and infrastructure defence.

Logically, governments would draw new “high water” lines on maps (based on whatever assumptions have been made about likely SLR encroachment over a given planning horizon) and limit development on the seaward side. In practice, a growing number of municipalities have attempted this and have in turn faced litigation by angry ratepayers whose properties fall on the wrong side of those lines, and are fearful about the impact to their asset values[9].

Miami Beach and Sydney Australia’s Collaroy Beach, which in the wake of a 2016 storm that saw an in ground swimming pool washed onto the substantially eroded beach, have taken the opposite route, investing in expensive protective infrastructure[10]. Elsewhere, beach “renourishment” and artificial reefs are being constructed to reduce coastal erosion.

Given events to date we predict the next few decades will be marked by cycles of “fight” adaptation, followed by an eventual, belated realisation that abandonment and retreat is the only sensible long term course of action. In this coming period there will be multi-billion dollar opportunities (trillions in aggregate) for infrastructure engineers and construction companies, funded by increasingly cash strapped municipalities and their alarmed ratepayers. And, as with drought assistance in Australia, state and federal governments will be forced to kick the tin.

At some point in the latter part of the century, unless by some miracle emissions are under control and planetary scale carbon sinks have turned net zero into net negative emissions, the coastal defence projects will be abandoned, prompting a new wave of infrastructure spend to move entire cities inland to territory deemed safe enough for the next hundred years or so. Exactly how that wave will be funded remains to be seen.

And it might not be the last. SLR doesn’t conveniently stop in the year 2100[11], though that is the current time limit of the most widely-reported projections. We may already have set in motion many centuries of ice melt, ultimately causing many metres of rise and eventually submerging hundreds of large coastal cities.

Of course, that’s just adaptation of coastal urban infrastructure to the effects of SLR. Fresh water and food production, public health and disaster preparedness are just some of the other areas that will face disruptive adaptation cycles. Smart companies will benefit by aligning their product/service portfolios.

- https://theconversation.com/carbon-emissions-will-reach-37-billion-tonnes-in-2018-a-record-high-108041

- https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/sep/23/countries-must-triple-climate-emissions-targets-to-limit-global-heating-to-

- https://cdn.gca.org/assets/2019-09/GlobalCommission_Report_FINAL.pdf

- https://www.miamiherald.com/news/local/community/miami-dade/miami-beach/article41141856.html

- https://www.tampabay.com/news/environment/2019/09/23/miami-beach-has-a-bold-idea-to-fight-sea-rise-turn-a-golf-course-into-wetlands/

- https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-08-05/wa-erosion-hotspots-named-port-beach-rottnest-island/11382136

- https://coastadapt.com.au/climate-change-and-sea-level-rise-australian-region

- https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/WG1AR5_Chapter13_FINAL.pdf

- For example, https://i.stuff.co.nz/dominion-post/news/wellington/115487741/wellington-report-2019-a-community-divided-on-what-to-do-about-coastal-erosion-sea-level-rise-and-climate-change

- https://www.governmentnews.com.au/coastal-council-a-crash-test-dummy-for-climate-change/

- https://phys.org/news/2018-10-global-sea-meters.html

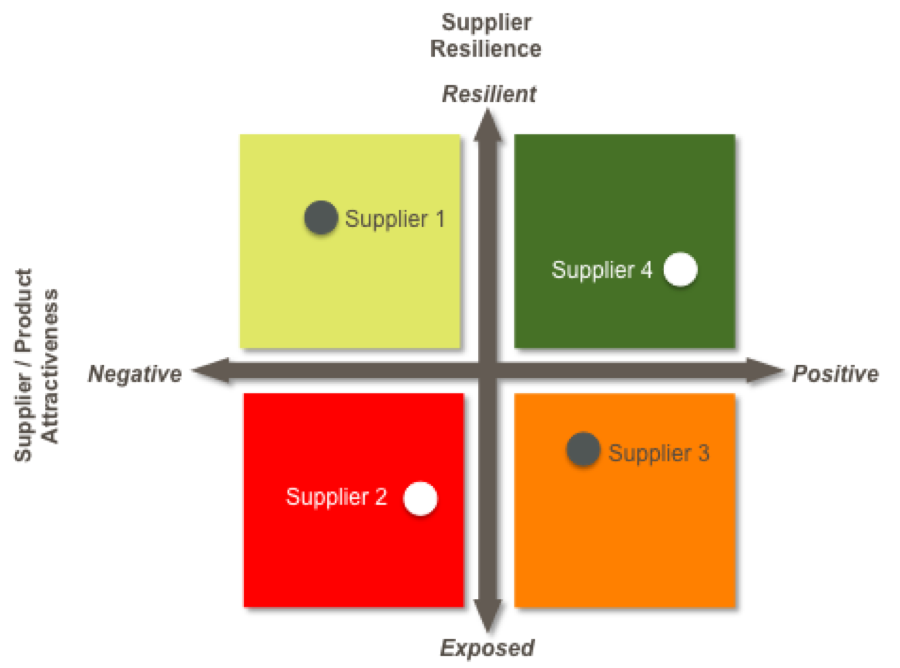

With major regulators making increasingly direct and clear statements about directors’ liability relating to the management of climate change risks, the “unforeseen” excuse is no longer going to cut it. In recent months major Australian regulators the RBA, APRA and ASIC have made it clear that the implications of climate change must be effectively considered in corporate decision-making.

With major regulators making increasingly direct and clear statements about directors’ liability relating to the management of climate change risks, the “unforeseen” excuse is no longer going to cut it. In recent months major Australian regulators the RBA, APRA and ASIC have made it clear that the implications of climate change must be effectively considered in corporate decision-making.